Rachel Wolfson-Smith: Behavioral Science

at Liliana Bloch Gallery

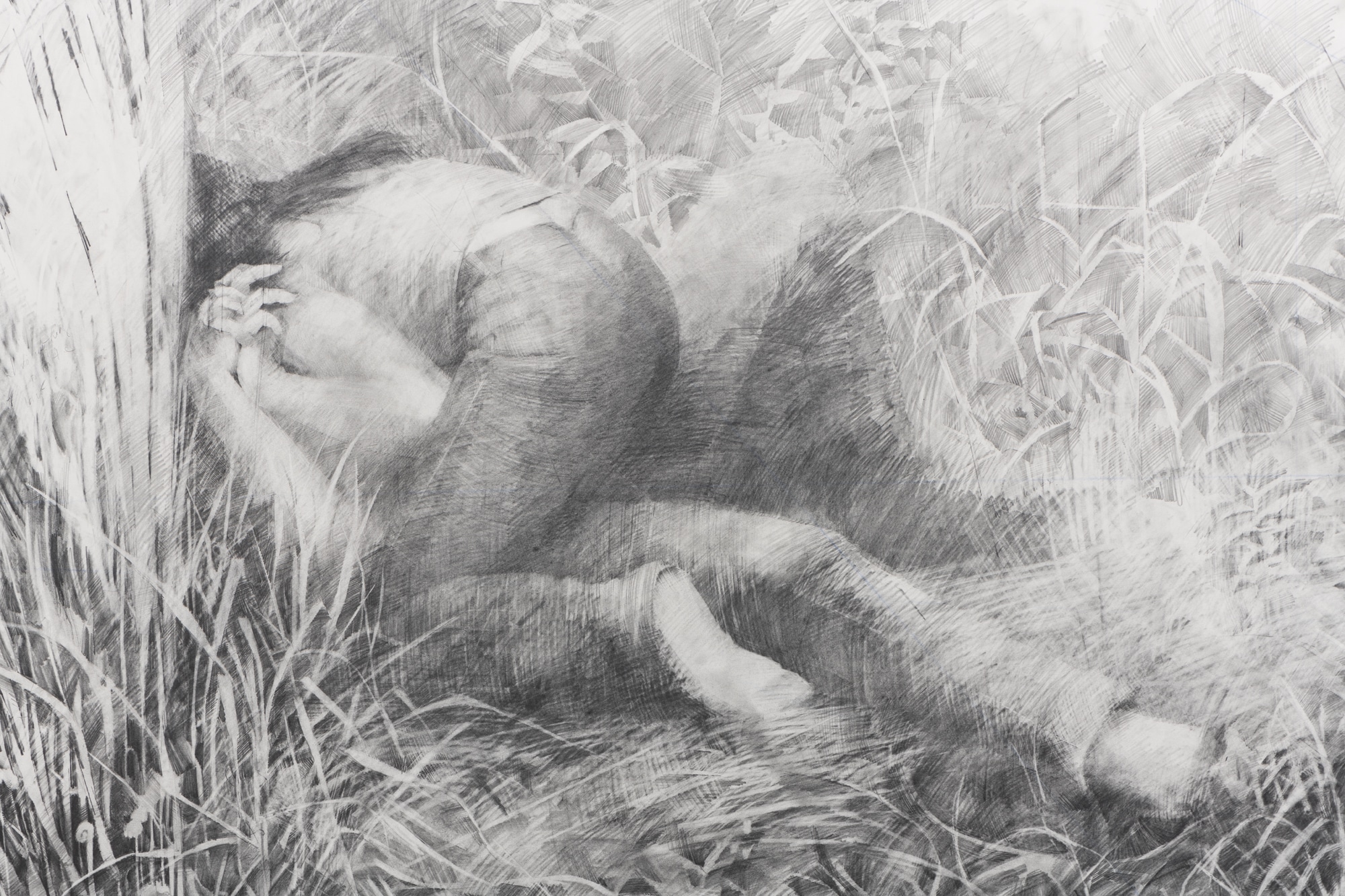

If graphite drawings could evolve, over time, into entranced photographs, they would likely resemble the work of Rachel Wolfson-Smith. Two of Wolfson-Smith’s 12 works on view at Lilian Bloch Gallery are the size of a movie screen, with a third piece nearly as large.

All are affecting yet confusing, a lot like the isolation we’ve all been experiencing at some level over the past two years, but here the handmade marks of a human holding a pencil turn so lively and exacting and in some cases, LARGE, that at first glance, they simply must be born of a machine.

The imagery suggests many things — imagined landscapes, secret hideaways, young lovers engaged in a romantic tryst — without relinquishing their own enigmatic power to envelope the viewer in profoundly personal emotion. But the smaller pieces conjure up associations just as engrossing, just as puzzling, where pristine detail gives sudden way to absence. If you adhere to the show’s curated layout in the gallery space, your experience initiates with the smallest work first, resulting in an elegant contextualization of Wolfson-Smith’s creative process before meeting the jaw-dropping larger works. But be warned: you will need a fair amount of self-restraint to let this adventure evolve to its own rhythm.

Wolfson-Smith is an American living and making art in Amsterdam, but her work has been shown and noticed all over Texas for the last five or six years (as well as a few places that are not Texas, like Istanbul). Her slightly blurred surfaces evoking leaves, sometimes with color, sometimes without, have a myopic, labor-intensive presentation that places the viewer just about anywhere — as long as the immediate, two-feet-in-front-of-you environment is natural, green, and hidden.

And while you’re in the gallery, be sure to spend some time with Tim Best’s collection of polaroids that share the hallway with Wolfson-Smith’s work. Best’s controversial vision of female objectification as a game involving complicity by the poser is undeniably humorous while unmistakably thought-provoking. Like Cindy Sherman, he employs himself as model in provocative poses, and the ensuing intimacy is both cheeky and uncomfortable as Best’s masculine-white-male-ness feeds unexpected tension to the simple act of a lover taking snapshots of a lover. Best dares to suggest that the intimate is not only universal, but unoriginal, and kind of fun.

feature: 2021 diptych – what he said – what she heard

view the shows at Liliana Bloch Gallery