LOST + FOUND: Colorizing the Skyline of Dallas

The mid- to late-1950s was a colorful time for downtown Dallas—literally! A wave of new tower construction hit downtown with colorful exterior designs not seen in this region before. Designs eschewed the masonry revivalist and classical styles of the past in favor of sleek and up-to-date design aesthetics featuring metal and glass curtain walls. Many designs featured a new trend in architectural exteriors: the use of porcelain-coated steel panels in a vivid array of colors.

Considering the number of buildings constructed with such panels, it was definitely a trend for commercial architecture. Two local companies helped to fuel the trend by manufacturing them right here in Dallas.

These two local sign companies—Texlite and McAx Sign Company—were the leaders in providing architectural panels for local construction. Texlite’s history as a sign company dates back to 1921 and they were responsible for creating the porcelain-coated steel Pegasus on top of the Magnolia building in 1934. The chief engineer for the Pegasus at Texlite went on to start his own sign company, McAx, with a new partner in 1946.

It was a logical extension of sign manufacturers to create architectural panels. They already had the technology down from making porcelain-coated steel signs and had the large ovens which could bake on the enamel finish in a dizzying array of colors—from neutrals to vivid saturated options.

All the Rage

Colored panels became popular for office construction in the 1950s with Eero Saarinen’s 1950 GM Technical Center in Michigan leading the way as one of the first well-known designs to use porcelain-coated metal panels as part of the curtain wall system. The use of the panels spread and many architects across the country incorporated them in their designs. Dallas picked up on the trend with numerous buildings constructed in that era using a variety of the fashionable colored metal panels.

Porcelain-coated steel was used before the 1950s for signs and small buildings like gas stations. It was even used in residential construction, as was tried by the ill-fated Lustron Corporation in the late 1940s.

One of the earliest buildings to fully take advantage of the color metal panels was actually outside of downtown. In 1955, construction started on the new terminal at Love Field. Broad & Nelson and Jack Corgan Associated Architects and Engineers boldly embraced the trend, using vivid green panels, alternating one light and one dark, across the majority of the exterior. It ushered in a new appreciation for the style and several large-scale uses of the panels followed in downtown.

The new Love Filed terminal designed by Broad & Nelson and Jack Corgan Associated Architects and Engineers opened in 1958 with vivid green panels, one light and one dark, used on the majority of the exterior. It ushered in a new taste for the use of colored panels in Dallas. Postcard image from Preservation Dallas.

Architect William Tabler of New York chose a bluish-green colored panel for his striking 1956 Statler Hilton Hotel design on Commerce Street. In 1957, George Dahl, FAIA also used blue panels for his Dallas Federal Savings building, now 1505 Elm. Aquamarine and azure panels were used in a checkerboard pattern for Thomas Stanley’s 1958 office building at 211 N. Ervay St. Thomas, Jameson & Merrill Architects went in a different color direction in 1958 with projecting copper panels mixed with stone panels and brick walls for the Relief and Annuity Board building at 511 N. Akard St.

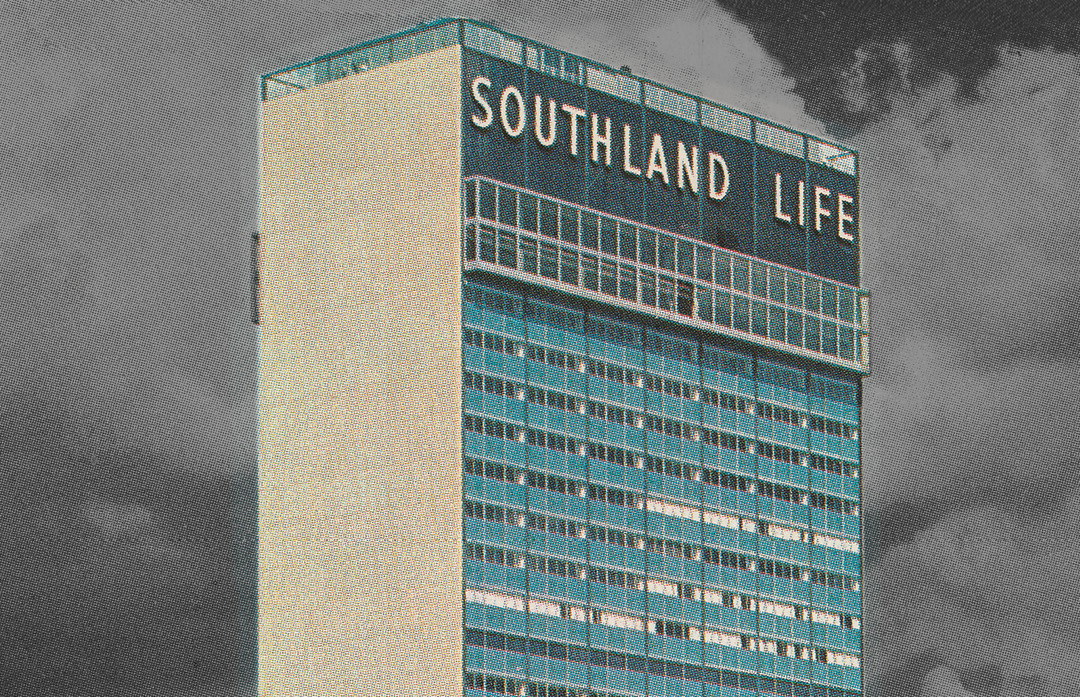

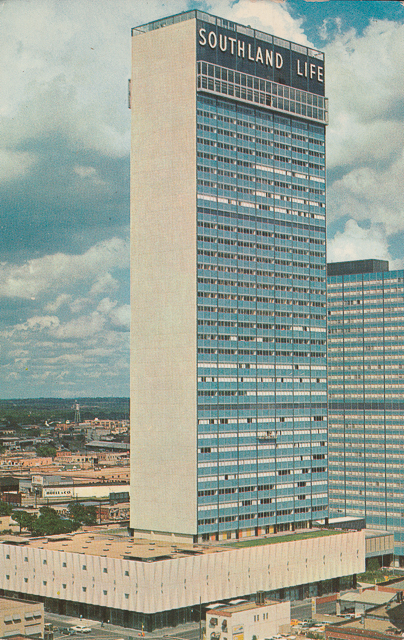

Not to be outdone by the other colored panel buildings, the Southland Center, now Sheraton Hotel, designed by Welton Becket & Associates was completed in 1959 with 42 stories of bright blue panels. It was the largest use of colored panels in Dallas. Unfortunately, those panels have since been toned down to a dull gray.

The Southland Center was the tallest building west of the Mississippi at 42 stories when finished in 1959. The architecture firm of Welton Beckett & Associates adorned the design with bright blue panels, which unfortunately have since been painted a dull gray. Postcard image from Preservation Dallas.

Dallas loves fashion and fashion trends, so it is no surprise that architects practicing in Dallas and their clients wanted the most fashionable and modern buildings possible. The colored metal panels helped these new sleek buildings stand out from the drab brick and masonry buildings of the first half of the 20th century. They provided a new optimism and forward-looking design aesthetic, fitting for the mid-century era. The splash of color was a welcome change for architectural design, and of course Dallas had to have the tallest example of it west of the Mississippi.

author: David Preziosi is the executive director of Preservation Dallas.

Originally published in Columns, a publication of AIA Dallas. aiadallas.org/columns-magazine