AUTHENTICATION IN THE ART WORLD

by Todd Camplin

Authentication has been in the news lately with artists that skyrocketed into fame and then they start to edit their past, authenticating one image and rejecting another. Take the case of Peter Doig, he believes he didn’t make an artwork and another person claims he did. So, the artwork has now been determined to be inauthentic by the courts. I, like other artists, have just thrown pieces in the trash that were just bad or experimental pieces that didn’t go anywhere. It is not unheard of for an artist to even ask someone to throw a piece out they gave a friend or family member. Foundations representing artists’ estates have also been known to be aggressive in determining authentic pieces and dismissing others. Historians, auction houses, and appraisers have all been caught up in the authenticating game. The problem arises when the client doesn’t like the answer to research and then takes legal action. This, of course, squashed people’s willingness to authenticate anything. But, when artists play with the idea of authentication, that is where it gets fun.

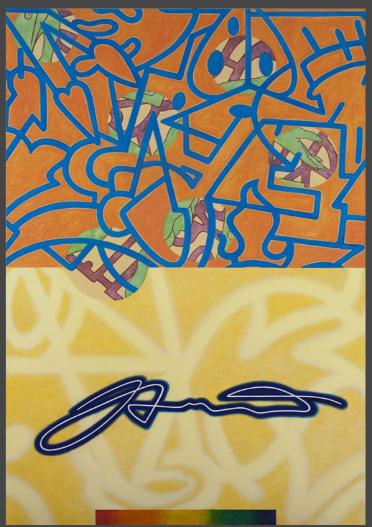

UTA artist Benito Huerta’s 2015 piece titled Signature Painting, or British artist Gavin Turk’s Unoriginal Signature drawings in the mid 1990’s seem to mock the idea of signature having the authority. Most of the big name post-war artists stopped the practice of signing the front, because the signature conflicted with what was going on in the painting. Signing the work on the front broke the spell of the painting and into that of the mythic artist. With a signature, the painting was not about the expression or image, but rather about the story of the artist. Many Postmodern writers took up the idea that artists as well as writers were attempting to make you forget the creator of the work, but rather immerse yourself in their work. Of course, the fashion of signing the front has not completely died, but most academically trained artists still follow

this tradition of signing the back. In fact, more professional artists create catalogs, numbers or some other organizing system that helps authenticate pieces. However, plenty of artists don’t bother.

Another artist that played with this idea of authentic art was Sol Lewitt. 105 wall drawings and paintings have been recreated from his instructions by a team of individuals at the MASS MoCA. These works were reproduced after his death, but yet these are authentically his art. How is this possible, because he believed that his art could be like sheet music. Follow the notes and you produce music in the same way if you follow his instruction you make his art.

On the less interesting side of things, a great deal of fabricated artworks are being produced for public art. Artists email their designs and a fabricator and engineer work out the production and installation. Some artists want to meet the demand for their work, so they produce work through a studio, rather than get their hands dirty. Nothing wrong with it, however, filmmakers give credit to all the people that worked on the film. How is it that the conceptual artist is any better than the filmmakers?

So, where does the drive for obtaining authentic art come from? And why do we value this experience over an inauthentic art work. After all, many museum goers don’t recognize the fakes from the real works. In the rare case, when an institution reveals a fake, it affects the mystique of the work and people feel less connected. Authentic experience of historical artworks is quite tricky and full of possible pitfalls. Maybe that is one of the reasons I enjoy contemporary art so much. You have the potential of shaking the person’s hand that made the art. You can’t get much more authentic than the experience of someone living, breathing, and telling you about what inspires them.

featured image: Benito Huerta – Signature Painting 2015